Cover Photo by Tom Dahm from Pexels

These skills will change your perspective on learning

Around this time last month, I started writing a complete guide on learning how to learn. It turns out, I was so inspired that the article turned into an 80-minute read — 20,000 words. I didn’t publish it, instead deciding to turn it into a book which I’ll likely release at the end of this month.

But I believed in the content so much that I also accidentally turned it into a course. If you know anything about me, you know I’m not a fan of courses in general. I like quick and actionable content, and most courses are not that. So, when it came time to design the course version, it had to be remarkable.

Today is the release day, but I don’t want to make this article a sales pitch. Rather, I want to give you quality content because I think it can greatly help you accelerate your learning going forward.

In this article, I’ll go over the 10 important skills taught in the course and explain some of the theory behind them.

1. Focusing

As a polymath, I like to do many things well. As a result, I start a lot of projects and try to bring them to a level I’m proud of. That’s a goal I rarely reach. To be really good at something, there’s nothing like giving it a lot of attention. If you do too many things, you spread yourself too thin.

I need to be reminded constantly that I’m doing too many things and I hate it. I often find myself working on twelve different projects at the same time (that’s no exaggeration). Most of the time, it’s not simple involvement either. Like, I’m the lead person on half of these projects, most of which are not short-term projects, like building a video game, writing a book, and growing a self-help business.

The only way I found to help me focus better is to raise my self-awareness. I won’t go into all the details here, but if you want to know everything there is to know about self-awareness, I wrote this comprehensive guide: How to Be Self-Aware — The Complete Guide

If you were to stop reading now and answering “why do I do what I do?” right this moment, could you answer with a single sentence? Most people can’t.

Before you can find out your why, you need to be aware of multiple aspects of your self. I like to make my brainstorming sessions easy, using simple lists. Here are some ideas to get you started.

List your:

Skills — things you do well;

Hobbies — things that occupy your time;

Passions — things you do for fun without external incentives;

Talents — things you learn fast;

Loved ones — people you care about;

Moments of happiness — key moments of your life or recurring events;

Moments of sadness — key moments of your life or recurring events;

Personality traits — things that define you as a person; and

Values — things you strongly believe in.

Once you have all the answers from your brainstorm, spend time to figure out how this all fits together. Move things in these categories (the four “what”s):

What are you good at?

What do you love to do?

What can you get paid to do?

What does the world need?

With the brainstorm from above and the answer to these questions, you might find something that comes at the intersection of your four “what”s. The answer might not come right away, but the more you do the exercise, the more obvious it will become.

2. Assessing Proficiency

A good way to assess if you’re good at something is to try to replicate something you already know is at the level you’re looking to get.

You can replicate art and music “easily”. For example, when I learned to play the Ukulele, my only goal was to be able to play Over the Rainbow at regular speed. If I could do that, I knew I’d be somewhere between beginner and intermediate in the skill.

If you try to replicate Leonardo Da Vinci’s paintings, you know you’re aiming for mastery.

If you learn to program, you could replicate a piece of software that’s known to be of the level you’re trying to reach. Like, don’t go replicate Google’s search engine if you’re a beginner. Here are 10 websites to get free programming challenges.

If the skill you’re trying to learn has clearly defined and replicate-able challenges for you to take, do it.

3. Progress Logging

Before you even start learning a new skill, think about what you want to be able to accomplish at the end of your practice. Always give yourself a deadline. Mine’s simple: I practice skills in chunks of 15 hours, broken down into daily 30-minute practice. I start on the first day of the month and end on the last day of the month. That’s always my deadline.

If you have less time to practice or you’re not sure you’re going to stay motivated for that long, simply set yourself a more reasonable deadline for you.

Set deadlines that will motivate you to take action on your learning and not discourage you. An approach I like to use is the SMART goals-setting approach — that is, make your goal:

Specific: direct, detailed, and meaningful.

Measurable: quantifiable or qualifiable.

Attainable: realistic for you given your constraints.

Relevant: aligns with your other goals.

Time-bound: has a deadline.

Once you have your overall result clear in your mind, start breaking into down into weeks of practice. What results do you want out of each week to reach your ultimate goal? If you practice is longer than two weeks, you’ll likely be wrong in your planning, but that’s fine. I adjust my plan on a daily basis to make up for that.

4. Habit Management

Here’s a template I built and use weekly for tracking habits:

Built in Notion

I rotate the habits regularly. Sometimes there are fewer, sometimes there are more. A lot of times, if I’m at the end of the day and I still have a few things to do, I feel an urge to check those boxes! It has been quite game-changing for me.

The hardest one from my list, as you might guess, is the grouping of all the bad habits into a single bucket. If I do a single bad habit on a given day, I can’t check that box. That, my friends, is hard!

“The difference between who you are and who you want to be is what you do.” — Charles Duhigg

5. Spaced Repetition

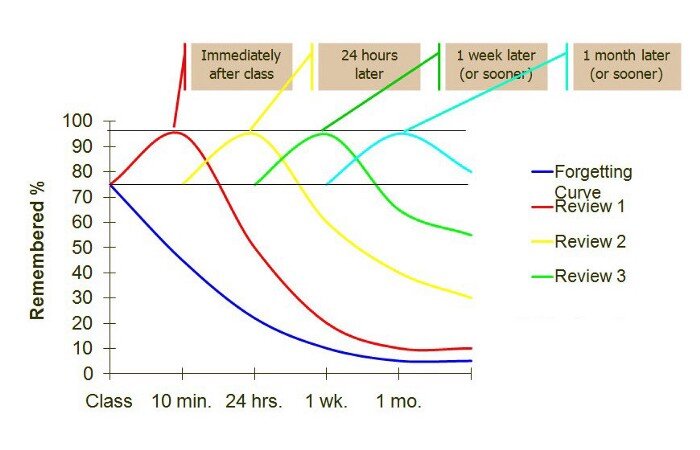

Take a moment to analyze the following graph:

If you do not recall what you have learned, you basically follow the forgetting curve. If you retain 70 percent of what you learned right after you learn it, within 24 hours you’re already at about 20 percent, and within a week, you’re at less than 10 percent.

This is cause for alarm, no?

Part of the reason you have homework in school is to partially help with that, putting you in the “Review 2” curve, increasing your retention by at least six times!

Isn’t it amazing?

So, when you practice something you’ve learned after 24 hours, then after one week, and then after one month, you’ll basically retain your learning for years to come. It takes such a minimal amount of time for you, yet the results are phenomenal.

So, the next time you schedule a learning session, think about spaced repetition and place “recalling sessions” in your calendar as well. That’s how, after not doing any video editing in a while, I’m able to just get back into it and remember how it’s done.

To help you facilitate the process, you can use apps like Anki.

6. Interleaving

Interleaving is a process where learners mix multiple topics during a learning session.

Let’s say you block thirty minutes of your time for learning. To interleave, you’d break into that between different but related topics. For example, if you want to learn the Spanish language, you could break down your learning session the following way:

Benefits

According to the University of Arizona, interleaving has been shown to:

be effective for developing the skills of categorization and problem solving;

lead to better long-term retention;

improve your ability to transfer learned knowledge; and

force your brain to continually retrieve.

Because each practice attempt is different from the last, rote responses pulled from short-term memory won’t work.

Here’s how you can get better at it:

Choose a few topics and disperse them throughout your learning sessions. The most efficient strategy is to use subjects that are related in some ways, like my example above.

If you’re interested in science, you could interleave by spending time in math, chemistry, biology, and physics, for example. For one learning session, you could practice in that order, but for another, you could reshuffle the order.

Doing that helps your brain not make the assumption that the material will always come in that order. The things you’ll learn in one topic may also be strengthened by another connected topic.

Essentially, changing things up forces you to retrieve information and make new connections between the topics.

7. Note-taking

Back in school, I was a lousy note-taker. Because I understood the concept in the moment, I figured there was no point take notes from it. I was wrong. When I started studying the topic of learning and the brain, I realized the importance of note-taking. Essentially, it boils down to two things:

The repetition or rewording of something makes the concept stick more easily

The more senses you involve in your learning, the better

The latter one is particularly interesting and one that’s often overlooked. To maximize the effectiveness of your learning, you want to involve as many senses as possible. If you’re just listening to a class in front of you or watching an instructional video, you’re using two senses: hearing and sight. The simple act of taking notes adds touch to the mix.

At the very minimum, you should note the concepts down. The idea is never to write down all the information you’re getting. You have to let your brain work a little with recollection. If you write everything down, it’s not any different from reading, and that’s mostly passive. To improve your learning, you can’t be passive!

Here are some forms of note-taking to consider:

Copying + pasting: Not effective

Highlighting text: Not effective

Transcribing: Not that effective

Flash cards: Effective

Review questions: Very effective

8. Mind-mapping

I started mind mapping seriously at the beginning of 2020 using the fantastic MindMeister tool. I now use it for two main purposes:

Making skill trees (see module 9); and

Here’s a simplified skill tree for the skill of Charisma:

Here’s a summary of a great article by Michael Thompson:

I now mind map all the time. The most important thing I found when mind mapping is defining a proper structure that’s both accurate and easy to understand for you.

Let me first start with important pitfalls of mind-mapping for skill learning:

If you’re studying a mind-map you’ve created when you were first learning, you might be studying content that’s not accurate.

Using only one resource to create a mind map only gives you one perspective, which may or may not be accurate.

Accuracy is so important because without it, you’re creating connections in your brain you shouldn’t be making. If I read in one source that pigs are blue and I’ve never seen a pig before, I’ll add it to the mind map, study it, and truly believe that pigs are blue.

9. Making Skill Trees

A skill tree is a visual representation of sub-skills required to learn a larger skill. It’s an ongoing document where you record your progress and learning material.

Skill trees help address learning pain points in three different ways, they: (1) raise your self-awareness, (2) channel your focus, and (3) guide your learning.

Skill trees raise your self-awareness because they force you to go deep into the sub-skills you’ve previously acquired and those you need to learn. When you build your skill tree, you map out all the sub-skills required, as well as your current proficiency level in each of them.

Once you’ve mapped everything out and you know how good you are at the different sub-skills, you can start to understand where your time should be focused.

And once you know where to channel your focus, you can start planning and executing.

The tool I’m currently using is MindMeister.com. You can also try the beta version of Ember.ly.

Skill Trees differ from regular mind maps because it’s not meant to be studied. It tells you what you need to get better at, but not exactly how. It’s a document you keep updating as your proficiency increases. You can even collaborate with others, but at its core, it’s all about YOU.

Here’s an example of the creation of a skill tree in a few steps:

Step 1. Define concepts, facts, and procedures. (Click to enlarge)

Step 2. Break things down into cohesive categories. (Click to enlarge)

Step 3. Self-assess your proficiency from 0–4 (Click to enlarge)

10. Visual Analogies

Photo by Ray Hennessy on Unsplash

If you look at the image just above, what do you think about? What do you come up with if you go beyond the obvious fact that it’s a turtle?

Have you ever noticed that you assimilated concepts easier when someones makes comparisons to things you already know?

I frequently provide analogies to help illustrate a concept. This is not by accident. They provide clarity or identify hidden similarities between two ideas. A good analogy clearly shows those connections. I use something you know and can visualize to illustrate a concept you may have never heard about.

Someone who masters the art of creating analogies is a great teacher. And when you know that you retain ninety percent of what you teach, you realize there’s a lot of value for yourself to learn to craft the right analogy. They are some of the best ways to teach yourself.

The best ones are timely and targeted. This is hard to do in writing unless you’re certain of exactly who your audience is. If you write about sports, making sports analogies makes a lot of sense. If you use an analogy about baking or about butterflies, you may puzzle your audience more than anything.

Conclusion

Learning these 10 skills can greatly improve your ability to learn other skills. If you learn them and become very good at them, you’ll start to learn faster, but also start enjoying the process of learning.

In the course, there are over 100 exercises you can do to get better at each of these skills. It’s broken down into 10 days, but you can go at your own pace. It also includes a learning plan worksheet, the SkillUp eJournal, and has a lot more content and accountability built in. Oh, and it’s very affordable!